Designing for Wildfires: The Importance of Your Neighbors, Sustainability, and Material Selection

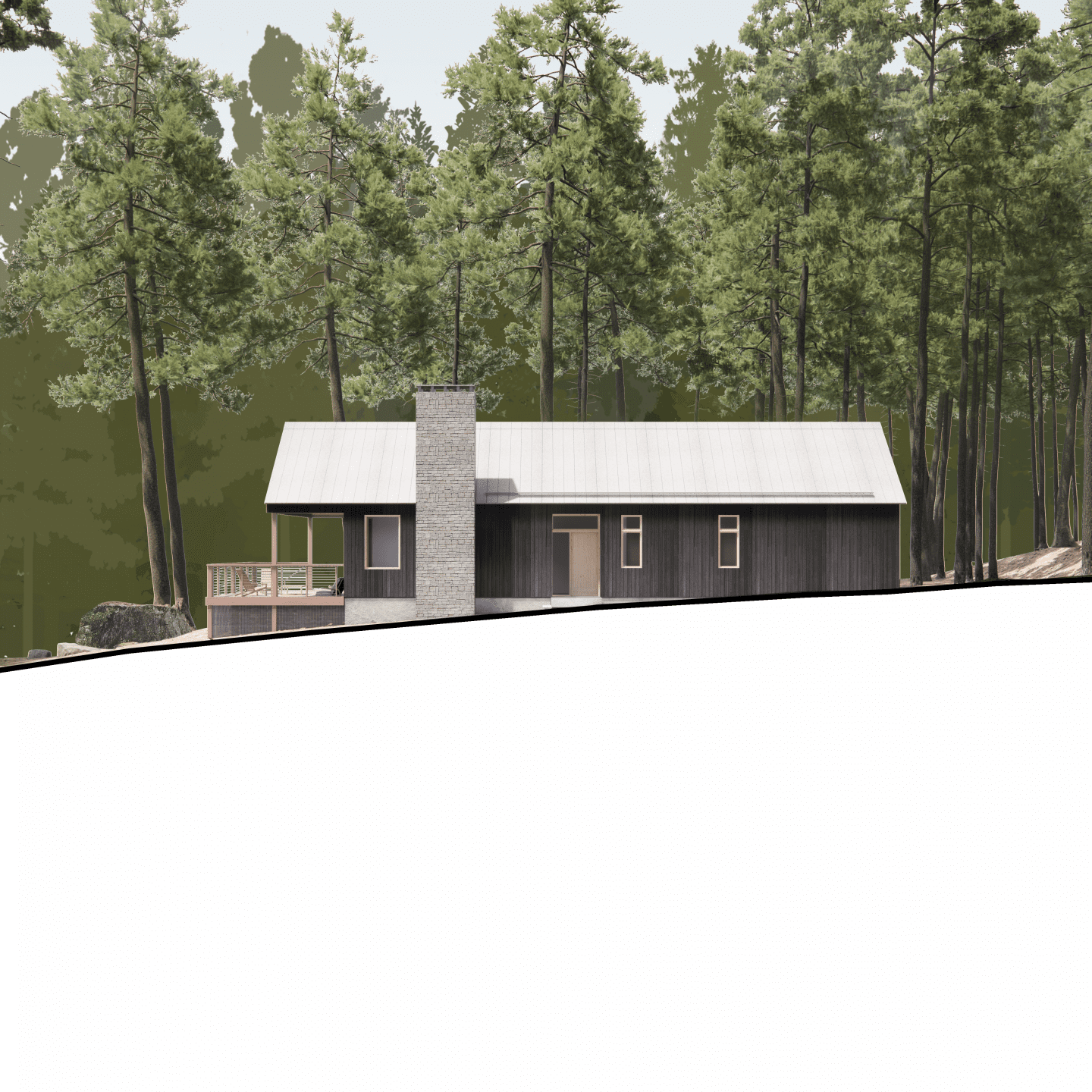

Year over year, wildfires are becoming a bigger factor in our lives, and this has to impact how we think about building design in rural lands. As we imagine ways to live and recreate in nature, our industry has always prioritized safety and endurance, but the rapid increase in fire damage and the size of the fires has prompted me to emphasize choices that can help prevent or mitigate damage. These considerations, both material and immaterial, can help plan for the possibility of fire to create smart, enduring spaces, whether for individual homeowners or for the community. I draw these lessons from Signal’s work with Oregon State Parks on the Cottonwood Canyon State Park’s Experience Center, completed in 2018, as well as from our ongoing work, including private residences located in the foothills of mountains in Washington State, Oregon, and California, as well as our work with parks organizations.

Site-Specific Design for Fire zones

Starting with a clear understanding of fire character and site factors, the surroundings of the site in fire-prone country are the most effective place to start. If the property is adjacent to wilderness, it’s important to limit dense vegetation, and manage understory growth and forest floor debris year-round to foster a healthy forest base when fire season arrives. Neighboring properties will have a direct effect on a structure during a wildfire, so working together with your neighbors to prepare could make substantial differences. For example, it’s a great start to separate fuel sources like propane, gas or other flammables from the structure itself, but if a neighbor hasn’t done so, it could invigorate the fire in an adverse way. The same goes for thoughtful landscaping that reduces or minimizes the ignitable ground surfaces around the home like drier, smaller bushes. Following guidelines for vegetation management will minimize fire spread at ground level and limit opportunities for smaller shrubs to ignite tree canopies. A mitigating precaution is the installation of rotary sprinklers, able to soak around the structure, to maintain a level of moisture unwelcoming to embers, as controlling embers can be one of the most effective tools to reduce ignition.

Some communities and counties in fire country foster partnerships–from neighbors and community groups to county and national agencies. Well-managed steps, informed by data, with clear instructions can provide a coordinated effort that serves the region. We have learned from our partners that understanding the ingredients for fire helps inform utilities, too, of the steps they can take to address it–before it happens. This site-specific data is a key step in reducing the very ignition of a fire. A wide-angle view of fire danger can apply to any scale of project. Where utilities consider miles of terrain, neighbors can evaluate and act on their adjacent properties, and work together through their neighborhood and community groups to engage in larger regional discussions.

Building Assembly

Once the site has been evaluated and prepared, designing a fire and heat-resistant building can actually borrow from sustainability approaches. Well-insulated walls and roof and double or triple pane windows will maintain lower interior temperatures, reducing the chance of ignition of the building from the inside. Air sealing–the method used in Passivhaus design–eliminates opportunities for embers to enter the building. Non-combustible siding will reduce opportunities for embers to ignite the surface, and reduce chances for the material to ignite due to heat from a nearby fire. Examples of especially resilient materials include metal siding, steel, concrete, stone, cement board panels, or fire-resistant, treated timbers like Shou Sugi Ban. Including a gypsum or plaster layer under the siding will increase the fire resistive characteristics further. The same considerations apply to decks, shelters, and overhangs, where opting for fire resistive materials with thoughtful detailing beneath will prevent a fire from carrying through to the structure. Fire suppression mechanisms like sprinklers inside the building can reduce loss and prevent flame spread if the building does ignite.

Site Selection

Planning for new facilities in fire country can utilize many of the steps listed above. Understanding recent fire history, site conditions, fire utilities, and current forestry management practices will help prioritize the prevention and mitigation strategies employed during design. If an adjacent area has recently burned, or has deployed forestry management or controlled burns, clear data and the level of local threats can be evaluated to determine the level of detailing. When locating a structure, understanding and incorporating local fire management access and maintenance practices will reduce risk and allow firefighters to monitor the forest and control a fire when it occurs. Orienting decks, open space, and resilient materials with consideration of prevailing winds and detailing the openings in the structure, such as attic vents and siding gaps will minimize opportunities for small embers to enter the structure. If a site has access to water, such as a creek, river, or lake, a pump and hose can be stored and periodically tested for immediate use against a fire.

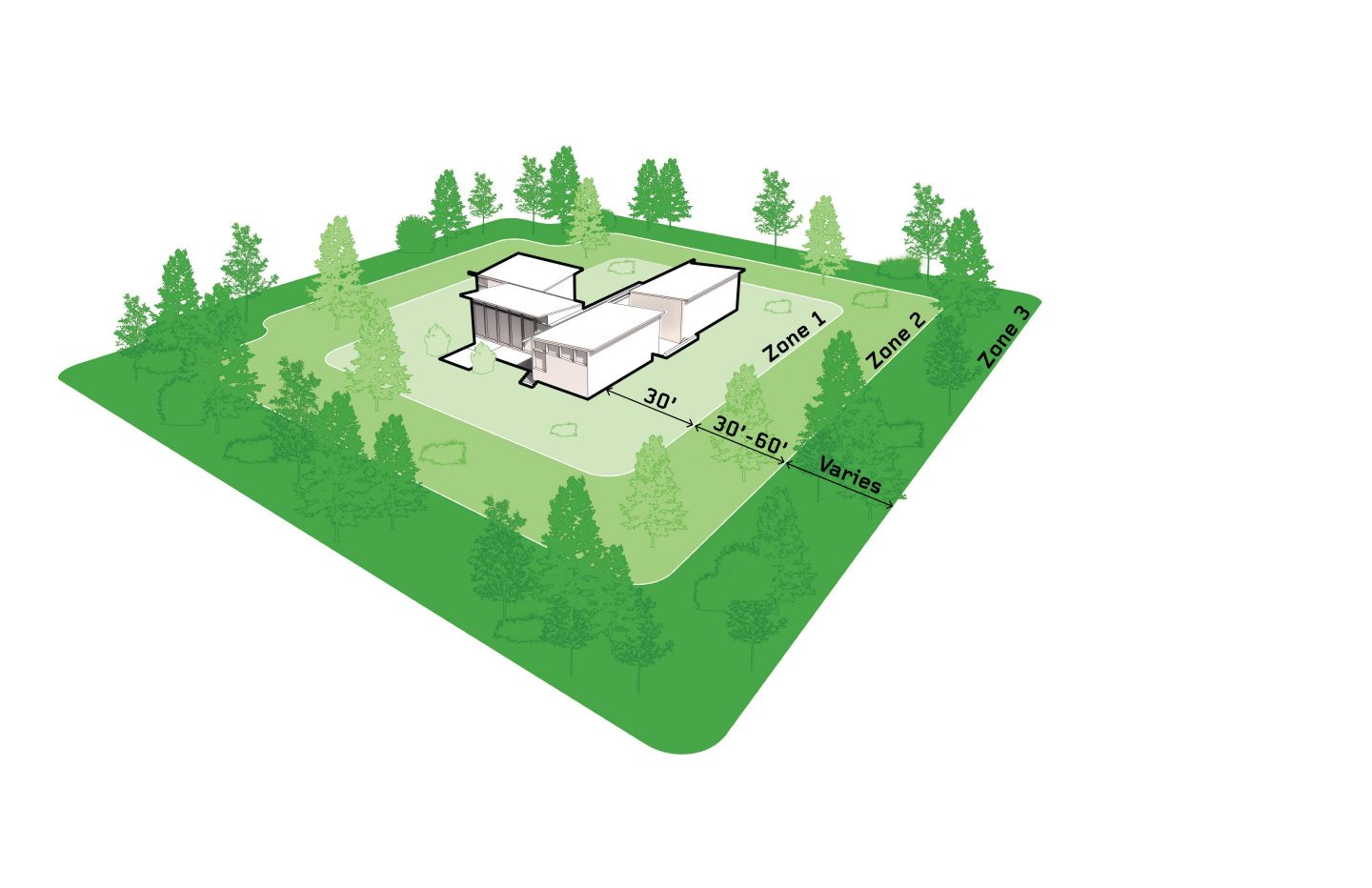

Defensible Zones

The area around the building is a critical line of defense for protection of the structure. This space next to the building can be categorized into three zones, each with best practice recommendations from multiple local and national organizations. Observing guidelines and coordinating site planning and ongoing maintenance of the property with the local jurisdiction or fire department will enable fire response teams to know what to expect and provide the property owner with some control over the dynamic nature of fire.

Zone 1: Within 30’ (10m) of the building. This is the area closest to the building–minimal vegetation should exist in this area, preferably limited to irrigated grasses. Driveways, patios, pavers, pools, and gravel are optimal surfaces. Potted plants that can be moved away from the structure in the event of a fire can create garden spaces. This zone should be swept clear of leaf litter, pine needles, and other vegetation debris by June 1 or prior to fire season as directed by local jurisdictions or community organizations. No fuel tanks or wood storage should be located in this zone.

Zone 2: The area that is 30’-60’ (10m-20m) from the building. Careful placement of shrubs and pruning and limbing of trees should be practiced. Wood storage and fuel tanks are permitted here, however they should be located away from trees if possible. This zone should also be swept clear of vegetative debris prior to fire season.

Zone 3: All areas 60’ (20m) or more from the structure. This area can remain natural, however regular maintenance to remove deadfall and standing dead trees, and managing extensive undergrowth will slow fire spread or ember ignition.

Wildfire is a dynamic threat on structures. While no structure can be considered fireproof, taking steps to understand the opportunity for file – fuel sources, fire personnel access, and surfaces around the building can create measurable results to reduce loss in the event of a wildfire. Resilience is critically important in fire zones–thinking beyond the property line to collaborate with neighbors and agencies to prepare for the worst can improve the outcomes when fire happens.

Sources:

https://www.fs.usda.gov/nac/buffers/guidelines/5_protection/11.html

https://www.readyforwildfire.org/prepare-for-wildfire/get-ready/defensible-space/

https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1652-20490-9209/fema_p_737_fs_4.pdf